George Saunders’s Ultimate Picture Book Reading List for Kids

by George Saunders

A version of this article originally appeared on Dinner a Love Story and was reprinted with permission.

Well, to start with, an apology/disclaimer: Our kids are grown and I’ve been away from kids’ books for a while (although I well remember the thrill, on a cold autumn night, of snuggling in with both our girls and feeling like: ah, day is done, all is well). Some of what follows may therefore be old news, but hopefully one or two will be new to you.

Let’s start with Kashtanka, by Anton Chekhov and Gennady Spirin (ages 9-12). I’ve written about this at length on Lane Smith’s excellent website, but suffice to say it’s a simple, kind-hearted story with illustrations that are beautiful and realistic with just the right touch of oddness.

Let’s start with Kashtanka, by Anton Chekhov and Gennady Spirin (ages 9-12). I’ve written about this at length on Lane Smith’s excellent website, but suffice to say it’s a simple, kind-hearted story with illustrations that are beautiful and realistic with just the right touch of oddness.

Speaking of Lane Smith (who is, to my mind, the greatest kids’ book illustrator of our time), Random House has just released a book the two of us did together, called The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip. Far be it from me to recommend my own book, but close be it from me (?) to recommend all of Lane’s books, and maybe particularly an early one, The Happy Hocky Family (ages 4-8). It’s funny and arch but also, at its core, an experience of real familial love. With Lane, every book has its own feeling, and this one’s is sort of minimal and yet emotive — right up my alley.

but close be it from me (?) to recommend all of Lane’s books, and maybe particularly an early one, The Happy Hocky Family (ages 4-8). It’s funny and arch but also, at its core, an experience of real familial love. With Lane, every book has its own feeling, and this one’s is sort of minimal and yet emotive — right up my alley.

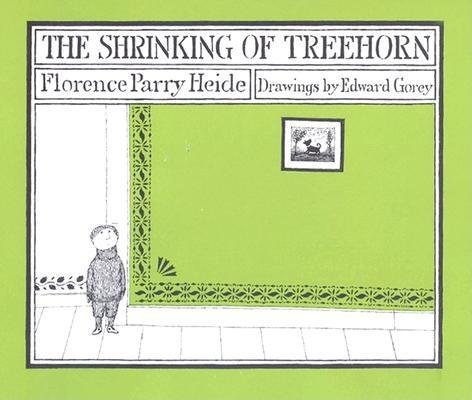

Back when we were doing our book (The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip, which I am not recommending, but just, you know, mentioning, because it has recently been re-released by Random House and all), Lane turned me on to The Shrinking of Treehorn, by Florence Parry Heide (ages 6-8). This is one of those books that stakes out its claim to greatness by showing something that, though harsh, is also deeply true: Grown-ups often don’t see kids and don’t listen to them. The illustrations are masterpieces of 1970s cool, by the great Edward Gorey.

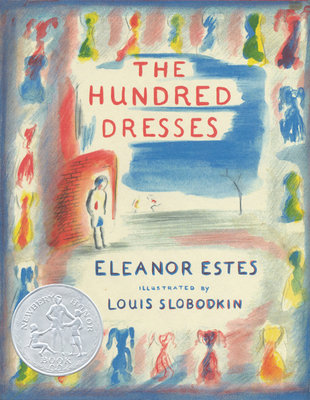

I love The Hundred Dresses, written by Eleanor Estes and illustrated by Louis Slobodkin (ages 7-9), for a similar reason. Using this ostensibly small palette of a kids’ book, Estes has conveyed a deep unsettling truth, one that we seem to be forgetting; as Terry Eagleton put it: “Capitalism plund ers the sensuality of the body.” Here, poverty equals petty humiliation, which drives a child, Wanda Petronski, to lie, and be teased for the lie, and then to create something beautiful — but the great heart-dropping trick of this book is that the other characters in the book discover Wanda’s inner beauty late, too late, and she is already far away, and never gets to learn she has devastated them with her work of art, and changed her vision of the world. This is a book that, I think, has the potential to rearrange a child’s moral universe in an enduring way.

ers the sensuality of the body.” Here, poverty equals petty humiliation, which drives a child, Wanda Petronski, to lie, and be teased for the lie, and then to create something beautiful — but the great heart-dropping trick of this book is that the other characters in the book discover Wanda’s inner beauty late, too late, and she is already far away, and never gets to learn she has devastated them with her work of art, and changed her vision of the world. This is a book that, I think, has the potential to rearrange a child’s moral universe in an enduring way.

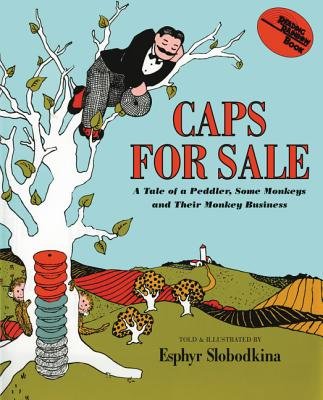

I also love Millions of Cats, by Wanda Gág (ages 4-8), for its eerie-funny Eastern European illustrations. I always mentally group this book with the equally Euro-Weird Caps for Sale, by Esphyr Slobodkina (ages 4-8). After the latter, you will never see monkeys the same way again. Well, unless the way you see monkeys now is as wily, acquisitive thieves and plunderers who should all be put in jail forever, no bananas.

I also love Millions of Cats, by Wanda Gág (ages 4-8), for its eerie-funny Eastern European illustrations. I always mentally group this book with the equally Euro-Weird Caps for Sale, by Esphyr Slobodkina (ages 4-8). After the latter, you will never see monkeys the same way again. Well, unless the way you see monkeys now is as wily, acquisitive thieves and plunderers who should all be put in jail forever, no bananas.

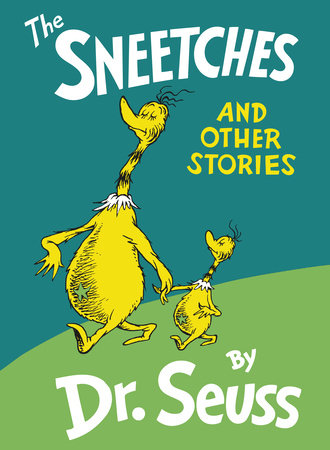

I love all Dr. Seuss, especially The Sneetches (ages 4-7) and the contained masterpiece, best if read in a quasi-Bela-Lugosi voice, “What Was I Scared Of,” which contains these classic lines:

I said, “I do not fear those pants

With nobody inside them.”

I said, and said, and said those words.

I said them. But I lied them.

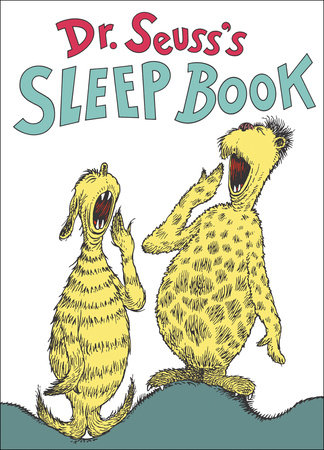

I also love Seuss’s Sleep Book (ages 4-7), which contains the immortal line: “And that’s why I’m bothering telling you this,” which comes in very handy as a sort of efficiency-mantra in graduate creative writing workshops, as in: Let’s not forget to always ask, “Why are we bothering telling us this?”

[RELATED: 15 Authors Share Their All-Time Favorite Bedtime Stories for Kids]

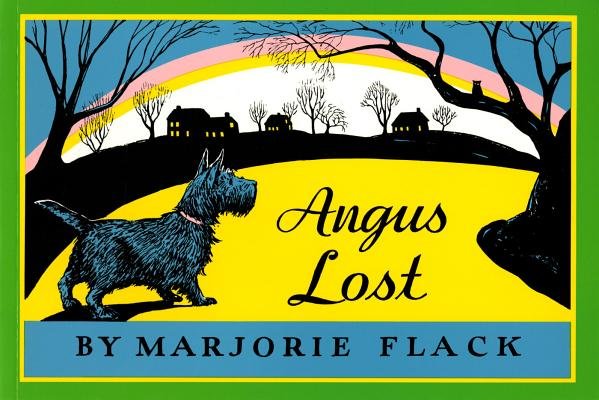

I really love Angus Lost, by Marjorie Flack, mostly because the typography and illustrations remind me, in  that weird way kids’ books can, of a time and place in which I never lived, but still somehow feel — in this case, a circa 1946 small town in, let’s say, Massachusetts. Plot: Angus, curious and world-hungry, leaves home, gets lost, and comes back home, a changed and gladdened dog. Which is, sort of, every life, in capsule, if we’re lucky. It also FEATURES these sporadic and very FUN-to-read occasional capitalized WORDS that you see NOW in screenplays, only here, in this book, they are saying “GRRRRUF” and “WIDE ROAD” as opposed to “SHOOTS,” “STABS,” or “WITH REAL SWAGGER!”

that weird way kids’ books can, of a time and place in which I never lived, but still somehow feel — in this case, a circa 1946 small town in, let’s say, Massachusetts. Plot: Angus, curious and world-hungry, leaves home, gets lost, and comes back home, a changed and gladdened dog. Which is, sort of, every life, in capsule, if we’re lucky. It also FEATURES these sporadic and very FUN-to-read occasional capitalized WORDS that you see NOW in screenplays, only here, in this book, they are saying “GRRRRUF” and “WIDE ROAD” as opposed to “SHOOTS,” “STABS,” or “WITH REAL SWAGGER!”

I’d also recommend The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (and listen to the Rabbit Ears audiobook featuring scary-as-heck music, great moody illustrations by Robert Van Nutt, and a masterful reading by Glenn Close) if you want to terrify your kids so much that they will never leave home or go outside in autumn and will totally forevermore avoid the Catskills. And pumpkins. And Glenn Close.

I’d also recommend The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (and listen to the Rabbit Ears audiobook featuring scary-as-heck music, great moody illustrations by Robert Van Nutt, and a masterful reading by Glenn Close) if you want to terrify your kids so much that they will never leave home or go outside in autumn and will totally forevermore avoid the Catskills. And pumpkins. And Glenn Close.

And speaking of scary, try The Gashlycrumb Tinies, by Edward Gorey, which is basically an alphabetical listing of twenty-six kids who died. Cheerful! “O is for OLIVE run through with an awl / P is for PRUE trampled flat in a brawl.” I see Gorey as a modern-day equivalent of the Grimms, whose message is cautionary more than reassuring. But there’s something so bold and sly about this book and the way that, as the alphabet progresses, the deaths get gnarlier (“Y is for YORICK whose head was knocked in / Z is for ZILLAH who drank too much gin.”) And little ZILLAH is shown solemnly drinking across a skeleton doll. Sleep tight, guys!

Joyful Noise: Poems for Two Voices , by Paul Fleischman, illustrated by Eric Beddows (ages 7-12), is very cool. The poems are presented in two columns; you take one part, the kid takes the other, and you do this sort of fugue-reading together. This, I promise, will bond you. Because even if done correctly, it’s sort of embarrassing. Your kid will see what you would have sounded like if you’d gone Total Thespian. But also, the two of you will occasionally blunder into moments of real beauty, and look at each other like: Whoa. And then go: MOM! (Or DAD!) Come hear this!

, by Paul Fleischman, illustrated by Eric Beddows (ages 7-12), is very cool. The poems are presented in two columns; you take one part, the kid takes the other, and you do this sort of fugue-reading together. This, I promise, will bond you. Because even if done correctly, it’s sort of embarrassing. Your kid will see what you would have sounded like if you’d gone Total Thespian. But also, the two of you will occasionally blunder into moments of real beauty, and look at each other like: Whoa. And then go: MOM! (Or DAD!) Come hear this!

When I was a kid, my grandmother had a bunch of those Little Golden Books around and these left a real impression on me. Whenever I rediscover one,  it sets off this synesthesia-like explosion of memories of Chicago in the early 1960s (Brillcream + lilacs + warm tube TV). I especially remember I Can Fly, and The Poky Little Puppy, and Mister Dog: The Dog Who Belonged to Himself (ages 2-4). There’s something about the design and colors of these things that you just don’t see anymore — each one its own little unlikely beautiful universe. I think that from these I learned that art does not have to be strictly representational to be deeply and lovingly about the world.

it sets off this synesthesia-like explosion of memories of Chicago in the early 1960s (Brillcream + lilacs + warm tube TV). I especially remember I Can Fly, and The Poky Little Puppy, and Mister Dog: The Dog Who Belonged to Himself (ages 2-4). There’s something about the design and colors of these things that you just don’t see anymore — each one its own little unlikely beautiful universe. I think that from these I learned that art does not have to be strictly representational to be deeply and lovingly about the world.

Dear Mili, by Wilhelm Grimm, illustrated by Maurice Sendak (ages 4-8), is a sad and deep little  book about love and loss and time — a book that is not afraid to go toward dark, nearly intolerable truths. I think one thing I look for in a kids’ book is an avoidance of a too-pervasive all-is-well outlook, mainly because it tends to be anti-literary. I mean, a happy ending is all well and good, but many of the books I’ve recommended here go at it in a more complicated way; they don’t flinch at ambiguity, assuming, correctly, that kids can not only tolerate complexity and ambiguity, but crave them, because in their hearts they know the world is big and scary, and crave sound counsel.

book about love and loss and time — a book that is not afraid to go toward dark, nearly intolerable truths. I think one thing I look for in a kids’ book is an avoidance of a too-pervasive all-is-well outlook, mainly because it tends to be anti-literary. I mean, a happy ending is all well and good, but many of the books I’ve recommended here go at it in a more complicated way; they don’t flinch at ambiguity, assuming, correctly, that kids can not only tolerate complexity and ambiguity, but crave them, because in their hearts they know the world is big and scary, and crave sound counsel.

Well, that and farting cats who wear suspenders.

If you want you r kids to read James Joyce one day and/or move to an organic farm in Iowa, you might turn them on to Rootabaga Stories, by Carl Sandburg. These are wonderful nonsense (although not quite nonsense — maybe more “near-sense”) prose poems that are great fun to read aloud. You can tell how fun just by the title of one story: “Never Kick a Slipper at the Moon.” This book is a great introduction to the idea that while literature is, of course, about what happens, it is also — and essentially — about how stories happen, i.e., in what language; and the reason we believe that they happen is, in part, because that language gives us pleasure.

r kids to read James Joyce one day and/or move to an organic farm in Iowa, you might turn them on to Rootabaga Stories, by Carl Sandburg. These are wonderful nonsense (although not quite nonsense — maybe more “near-sense”) prose poems that are great fun to read aloud. You can tell how fun just by the title of one story: “Never Kick a Slipper at the Moon.” This book is a great introduction to the idea that while literature is, of course, about what happens, it is also — and essentially — about how stories happen, i.e., in what language; and the reason we believe that they happen is, in part, because that language gives us pleasure.

And finally, in that spirit (the spirit of sound counsel, not the spirit of a suspender-wearing farting cat), Once There Was a Tree — by Natalia Romanova, illustrated (again) by Gennady Spirin (ages 4-7) — is a weirdly Zen eco-tale that doesn’t rush to any conclusion. And the illustrations make me want to move to Russia. In the nineteenth century.

Let me close by saying, from the perspective of someone with two grown and wonderful kids, that your instincts as parents are correct: A minute spent reading to your kids now will repay itself a million-fold later, not only because they love you for reading to them, but also because, years later, when they’re miles away, those quiet evenings, when you were tucked in with them, everything quiet but the sound of the page-turns, will seem to you, I promise, sacred.

-

Books Mentioned in This Article:

-

The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip

Also available from: -

Millions of Cats

Also available from:Caps for Sale

Preorder from:The Sneetches and Other Stories

Also available from: -

Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book

Also available from:Angus Lost

Preorder from: -

The Poky Little Puppy

Also available from:Mister Dog

Also available from: -

Rootabaga Stories

Preorder from:

George Saunders is the author of nine books, including The Lincoln in the Bardo and the story collections Pastoralia and Tenth of December, which was a finalist for the National Book Award. He has received fellowships from the Lannan Foundation, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the Guggenheim Foundation. In 2006 he was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship. In 2013 he was awarded the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in the Short Story and was included in Time’s list of the 100 most influential people in the world. He teaches in the creative writing program at Syracuse University.