How Fantasy Novels Help Kids Explore the Messiness of Real Life

by Matthew Cody

“Fantasy” is a bad word. Not in its everyday use, mind you. I don’t dislike it at all when I’m dreaming of a quiet beach while stuck in a crowded subway car or practicing my acceptance speech for a big award. Fantasy is just the word for those moments. The use of “fantasy” that I take issue with is the way it’s applied to books. Fantasy as genre. Ugh. Pair it with the even more disreputable “escapism” and I’m done. Thanks. Goodbye. So long.

So if fantasy isn’t my thing, what sort of stories do I like? Well, let’s see. I do like the odd ghost story. Oh, and I love stories about magic, other worlds, heroes, and monsters…

“What a minute!” you shout (hopefully not too loudly, because I’m right here). “You just said you hated fantasy and yet all that stuff you just listed is absolutely fantasy!”

Ah, yes, I guess it is. My bad. Let me restate my opening thought: “Fantasy” is a bad word when used to describe a particular genre of writing, because it comes loaded with the connotation that it is not about reality. And this attitude goes doubly so for kids’ literature, where fantasy is interpreted as a “safe zone” for young readers, where the author leaves the icky messiness of real life outside the wardrobe door. But not only is leaving out the icky messiness of real life unwise, it’s pretty much impossible. The icky messiness is what it’s all about.

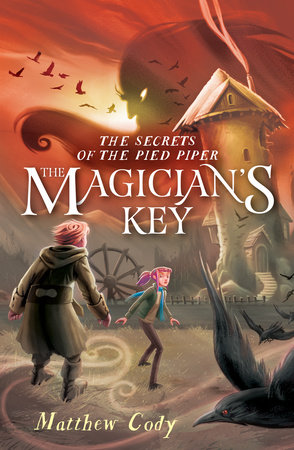

Recently, Kirkus Reviews said something about my middle grade novel The Magician’s Key that got me thinking about this whole topic in the first place. For context, The Magician’s Key is the second novel in a trilogy about a brother and sister on a quest to rescue the lost children of Hamelin from the clutches of the legendary Pied Piper himself. Along the way, the enchanted isle the lost children have been living on erupts into war, while back on earth the sister tries to lead a hidden society of magical beings to a place they can finally call home. Got it? And here’s the line from Kirkus that I mentioned:

“The intersection of magic and modernity provides an interesting forum for the discussion of racial profiling, disenfranchised individuals, and the effects of evil in the world.”

First off, um, thanks? Second, that’s … a lot. Let’s assume that The Magician’s Key is fantasy. In fact, it’s got all the fantasy: magic (check), other worlds (check), and giant rats with knives (pretty monstrous, right? I’ll give myself another check). But racial profiling and disenfranchised individuals? Where’s the escapism in that? Where’s the safe zone?

When I was writing The Magician’s Key, our world was just beginning to pay attention the depths of the refugee crisis caused by the wars in the Middle East. The horrific pictures were everywhere, in the papers, on TV, and on social media. And while I honestly never intended to write about current events, it ended up on the page anyway. I wrote about war and the plight of immigrants and the dispossessed, but it just so happened that my subjects were elflings and goblinfolk … and children.

By the time I finished the first draft, the news had gotten closer to home with debates over immigration and borders. And at the same time my whimsical fantasy novel had become about a whole class of people, in this case magical beings in hiding, willing to give up everything for a shot at a better life.

Ah, I know what you’re thinking: politics in my fantasy? But no, I don’t think so. And I know most of my young readers won’t think so either. Because here’s the great thing about kids: They have a righteous sense of fair play that transcends politics. They see the world around them, they glance through the newspaper headlines and the tweets, and they hear the TV on in the background, but they don’t know or care about the politics of a problem like the refugee crisis. All they see is that someone is suffering and the strong are preying on the weak.

Thankfully, kids don’t need to come up with solutions to the world’s problems (that’s up to us big folk) but that doesn’t mean they don’t still think about them, and worry.

That’s where I think that old bad word can be useful. Fantasy is the safe zone, but not to escape from the problems of the world, rather to explore them in a safer context. It’s a zone where the young reader can engage with big problems — sometimes scary — that they are a part of anyway, like it or not. Fantasy pulls the neat hat trick of rewarding the reader’s empathy while reassuring them that good can prevail in the end. It empowers them to think about big ideas without overwhelming them.

So fantasy not as an escape from reality, but as a different way of engaging with it. Escapism from the glare of headlines and roar of the scaremongers, but not from the trials and tribulations that join us together and make us human. Fantasy stories are stories that mean something, even for children. They’re just filled with cool stuff like trolls and witches and magic swords.

Fantasy. Maybe not such a bad word after all.

-

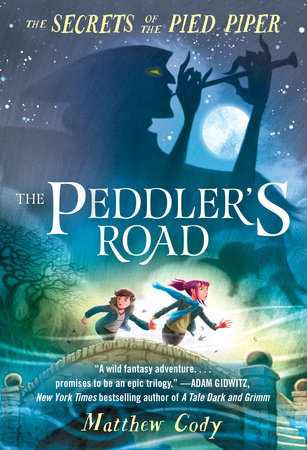

Books in the Pied Piper Series:

-