How Reading Picture Books Helps Me Cut Through the Noise of Autism

by Naoki Higashida

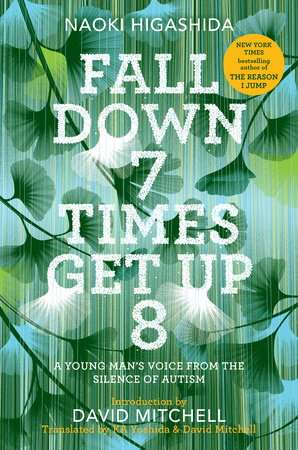

Naoki Higashida took the world by storm with The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy with Autism. The bestselling memoir, which he wrote as a young teenager, reshaped the way people think about autism. With one groundbreaking book under his belt, Higashida recently released his sophomore effort, Fall Down 7 Times Get Up 8: A Young Man’s Voice from the Silence of Autism. The following is an excerpt from this new book, in which Higashida describes the moment when reading picture books “clicked” for him as a child with nonverbal autism and how that experience has profoundly impacted him.

Sometimes my helper and I go to the local library, where I sit myself down in the children’s section and go through picture books. The ones I read are pretty much always the same; in fact, since childhood, the repertoire has hardly altered. I prefer to think this is not owing to limited intelligence; rather, it’s because when I read them, my mind goes wandering off inside the world of the picture book and I can freely, safely, unwind. Here in the real world, there aren’t many places where I and my autism can lower our guard. Like flowing water or the texture of sand or the beauty of light, my favorite picture books afford me a therapeutic comfort.

When I was really little, oddly enough, picture books left me cold. Mom would try to read them to me but I’d just run off — it really did her head in! My knowledge of words was so scant that my mother reading a picture book to me was just another noise — like the sound of lots of people talking all at once. Picture books might look very simple but they require imagination to work; and since I showed zero response to any picture book of any kind, I caused my mother a great deal of worry — so I’m now told. One day, however, she noticed how often I was looking through old photographs. So Mom put together a photo book using our family pictures, and wrote short sentences alongside the images. It was thanks to this that the whole point of picture books “clicked” for me, and from then on the number that I enjoyed steadily grew. Also, I could begin to relate my everyday self to the characters in the books.

Conventional wisdom has it that people with autism have little interest in other people and little understanding of other people’s emotions. I’m no longer so sure about this. One day, I suddenly became aware that Mom wasn’t around and — jolted — I set off in search of her. She was only upstairs, but she was surprised that I’d come looking for her. Previous to this, it had always been my mother who was wondering where I had wandered off to. I’d never searched for anyone else out of anxiety for them as opposed to wanting something from them. I had always existed in a world with just one principal character, much like the world of a picture book. Life for people with autism can be like this, and if only a day could pass as effortlessly as the turning of a page, we would be content. However, this isn’t the same as being incapable of compassion or sympathy. The Naoki who was worrying about where Mom had gone was a Naoki who had jumped out of that picture-book existence. I know I’ll never be like anyone else straightaway — if ever — but little by little, I intend to write my own story.

-

Fall Down 7 Times Get Up 8: A Young Man's Voice from the Silence of Autism

Available from:Also available from:

Excerpted from Fall Down 7 Times Get Up 8: A Young Man’s Voice from the Silence of Autism by Naoki Higashida, with the permission of Random House, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2017 by Naoki Higashida and David Mitchell.