Body Positivity Starts With Parents

by Laura Zimmermann

I am pleased with myself, checking off boxes on the imaginary body-positive parenting scorecard I invented. If I can get them all, I’ll win the Most Emotionally Well-Attuned Parent/Body-Image Category (my imagination is competitive).

- I regularly remind my family, sometimes unprompted, that no body type is better or more beautiful than another.

- I am careful never to utter a shaming word, and to only follow Instagram celebrities whose bodies don’t conform to unrealistic standards — never the ones that are Photoshopped into impossible alien proportions.

- I regret calling them “alien proportions,” even if they are totally fabricated by fashion designers, because it still sounds like shaming.

- I talk with my daughter about what her body can do, rather than how it looks, and even though no one told me to, I talk to my son, too. (I give myself extra points for knowing that boys face pressures about their bodies, too.)

- I never call a baby “cute,” even though it is the only thing you can tell about a sleeping baby. I say that it must be quite clever and I hope it will grow up to love itself. The parents stroll away offended, but deep down the baby feels respected.

- I even chide my daughter’s friends for calling my political nemesis “orange,” because it is actions and words we judge, not appearance, and that is hard because I really want to say he deserves it.

But there is an empty box left on the list. That one is not about anybody else’s body. It’s the one about my own.

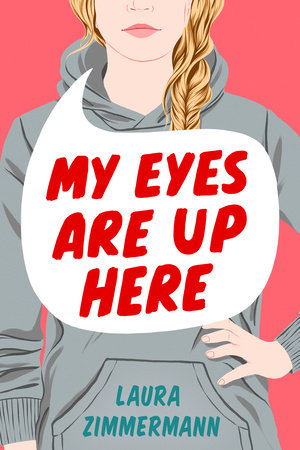

My YA novel, My Eyes Are Up Here, is about Greer Walsh, a high school sophomore whose self-assuredness has veered way off course as her body has radically changed proportions. In her case, the issue is that she has developed breasts that are much larger than those of her peers, and the way she feels about her body — and the way other people seem to feel about her body — has locked her in a state of being perpetually uncomfortable.

While I was working on the book, I spent a lot of time observing both overt and more insidious ways people communicate their biases about bodies. It’s not always about weight or shape (though those ideals were wired into many of us since we picked up our now-dèclassè Barbies); it also shows up in barely conscious reactions to height or facial hair or complexion. It shows up as veiled concerns about “health.” It shows up in our assumptions about who should wear what or move how. Unlearning takes time, and it’s both infuriating and humbling when my teenagers point out my misses.

One thing that I noticed, however, is that even among the best-intentioned parents — those who swear to champion body diversity and keep a self-congratulatory scorecard — we rarely hesitate to complain about our own bodies. “I look HUGE,” we might say. “I know it’s just the grocery store but I can’t go out in these leggings!” “Can’t you crop me out of that?” And we say it all in front of those same children whose bodies we are so diligently protecting from self-doubt.

I’ve deleted family photos because my arms look fat, then undeleted them because there’s no picture of all four of us at Stonehenge. I then found one where I’m mostly behind my son, who is half blinking, but he is still adorable because he is my son. He’s adorable while looking like he got a shot of Novocaine in his eyeball, and I’m hiding my not-awesomely-jacked arms behind him. Very consistent, Mom.

Have you ever tried to explain a Spanx onesie to a six-year-old while you’re putting on a Spanx onesie? “It smooths out Mommy’s lumpy bits. No, lumpy bits aren’t yucky. They’re just, um, lumpy. Wait. Let me start over. This dress is a little tight and some bellies—most bellies—aren’t naturally flat, and they don’t have to be, but after I had you… no, I’m not mad at you, sweetie. Actually, you know what? It’s for back support.”

Even if we get everything else right (which we won’t), how can we teach our kids to love an infinite range of possibilities for their own bodies if we’re still so unforgiving of our own?

It’s complicated parenting gymnastics, to be sure (particularly in Spanx )… and I don’t have a good solution.

In the book, Greer doesn’t suddenly overcome all her insecurities at once, either. She tries some things she hasn’t tried before. She goes out for volleyball. She meets a boy. She takes a couple of steps forward and a step or two back. She discovers other people — a teammate, a tailor , a YouTuber — who are unapologetic about their bodies. She pays attention to them. She stands up straighter (literally and figuratively).

What she doesn’t do is wake up one day, don a bikini, stand on a lunch table, and demand to be seen. She doesn’t win the Body-Positive Teen category. What she does do is decide that she’s not going to let being uncomfortable get in the way of who she really wants to be. It’s a start. A good one.

And maybe we can start there, too. Not with utter enlightenment, but with understanding. With posting fat-armed photos, even if you don’t love them yet, because you were all at Stonehenge together and that’s what you want them to remember. With jumping off the diving board in last year’s too tight swimsuit, because it’s really damn hot and it would break your heart if it was your child hiding under a beach towel. With letting your Bitmoji go gray when you do, and laughing with your kid when you get tangled up in your Spanx. It’s not about keeping a scorecard or trying to win body positivity, but about showing up to play.