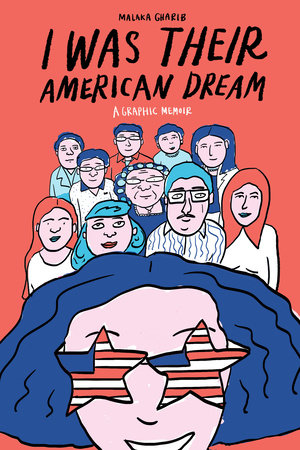

Everyone’s Story Deserves to Be Told: Malaka Gharib’s Version of the American Dream

by Laura Lambert

Who gets to be American? That’s the question at the heart of NPR journalist Malaka Gharib’s debut graphic novel, I Was Their American Dream. It’s the story of her unique childhood — half Egyptian, half Filipino, growing up in one of the most diverse suburbs in the nation, Cerritos, and then moving out into a wider world where diversity looks — and smells, and sounds — a lot different. Over the course of 160 pages of her own drawings, Gharib begs the question: aren’t we all American, if we are here in this melting pot — or salad bowl, or whatever metaphor you prefer to describe our rich, multicultural nation? And don’t our stories deserve to be told?

Brightly spoke with Gharib about the importance of seeing yourself and your experience reflected in the books we read.

I laughed so much reading your book — in recognition. I’m half Korean. I grew up eating food other people thought was weird. I even have all these Korean cousins from Cerritos! And then I realized how rare it is that I get to see that aspect of my life reflected back at me, in any way, shape, or form. Is that why you wrote this book?

Definitely. In 2016, there was so much anti-immigration rhetoric, and the generalizations about immigrants was surprising to me. I felt like it was the result of not talking about our cultures openly. If people only knew how I grew up, they would have a more nuanced view of who immigrants are. I started sharing stories of my parents and family on social media and it resonated with a lot for a lot of people.

Who is this graphic novel for? It definitely speaks to me, but I imagine it speaks to a younger audience as well.

I have two audiences in mind. I wanted it to be for other people of color who grew up in this country, so they understand that their stories aren’t crazy. People are struggling through this identity crisis – I want to be American, but I don’t know what that is exactly. If I’m brown and living in this country, doesn’t that make me American, too?

This is also the story I wish I could tell my white friends. In college, I got so many comments about my English! They’d say: “Oh, you pronounced that word wrong.” Well, if you only knew how I grew up you, with two non-native English speakers at home, you would understand.

Your formative years were in California in the 2000s, where — as you point out about your high school — diversity was a given. Was that a blessing, or a curse?

I think of it as a blessing. It showed me that we have to be sensitive to people’s ethnicity and background. There’s a difference between Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi kids. It’s important to know the distinctions and the differences. Each of these peoples take pride in their ethnicities. When people generalize, it’s like running a bulldozer over your whole identity.

Is there a through-line from producing zines to this book? Does this feel like a natural extension of the personal storytelling you were already doing?

I was heavily into the American Girl books and the Amelia’s Notebook series. The American Girl magazine always talked about girls from different cultures, and I wished they would have one for Egyptian Filipinas. That’s sort of what this book is, if there ever was an American Girl book about me.

And it’s a natural extension of my zine and of my journal. I’m always drawing a lot of cartoons.

I love that your book references Felicity as well as what it was like “vacationing” while the Second Intifada rages 30 miles away — pop culture and history, all in one. Can you tell me a little more about the importance of having both in the same book? Is it just a reflection of your personality, who you are?

Pop culture and historical moments shape the decisions one makes in life. When you think about the forces at work, they are as mundane as Felicity and as heavy as the 2008 economic recession. The economic recession is why I started my career. Felicity guided me to New York. The Second Intifada — and my experiences in Egypt, the poverty I saw there — encouraged me to have a career in global development and journalism.

And what does your world look like now, in Washington D.C.? Is it as diverse?

I don’t think it’s diverse, not when you think of Cerritos or L.A. If I want to find a more diverse group, I have to go out of my way. I saw a Filipino man walking down the street, and was like, Another Filipino! I made business cards later, saying, “I’m ____, too. Let’s be friends!” with my phone number and my email.

I have to seek those out, make my own home. I joined an Arabic class. I started a Filipino food lunch club at my office. I’ve been living away from home since 2008. As I realize that I’m probably going to be in D.C. for a while — I’m married, I have a house, I have a career — I know it’s no one’s responsibility but my own to bring the elements of home and my identity here.

You recently tweeted about getting a review from a Bangladeshi-American middle school student in Boston — that feedback from young people has been the most rewarding. Can you tell me more about that?

She’s from Bangladesh, and everyone assumed she was Indian. She said, people don’t ask me, and if they do, they don’t know where Bangladesh is. That cultural awareness is important for me. You want to feel like your culture matters and is worth talking about.

What have you read lately where you’ve felt that glimmer of recognition — where you’ve felt seen?

Esmeralda Bermudez at the Los Angeles Times did this video story on Vicks’ VapoRub. Oh my god, that was really, truly emblematic of the immigrant experience!

Our immigrant parents who moved to the U.S. had kids who have grown up. And now we’re writing about the stuff that we care about. It’s being reflected in the media all over the place. The video just made me see the potential of an America where our stories were represented. It’s very beautiful and moving.