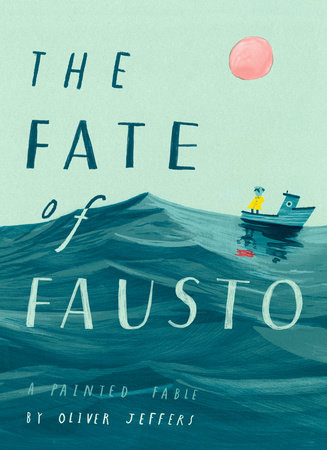

Dark and Complex: The Fate of Fausto Is Classic Oliver Jeffers

by Jennifer Garry

The first time I read The Fate of Fausto by Oliver Jeffers, I was left with my jaw on the floor. My mouth literally flopped open. Then I read it again. This time, I was left with the familiar feeling that generally washes over me after reading one of Jeffers’ books. I’m not exactly sure what the word for it is. It’s a gradual warming that opens up and unfolds into understanding until I’m left nodding my head slowly and saying, “Yes.”

Jeffers is the king of unraveling stories with layers that mean something slightly different depending on where you are in life. Some of my favorites from the Northern Ireland-born artist and storyteller teeter precariously between being for children and adults, landing firmly in a category all his own (The Heart and the Bottle is about finding joy after loss; Here We Are is about being a human on this planet — and is written from the perspective of a new parent). His newest book, a fable made with traditional lithographic printmaking techniques, is no different.

Fausto is a pompous jerk. Greedy and self-important, he thinks he can and should own everything he sees. “You are mine,” he declares to flowers and sheep and trees and forests.

They all oblige, leaving him haughty and satisfied, his nose lifted toward the sky. A lake and mountain fight back a bit, but all it takes is some stomping and shouting and they too bend to his will.

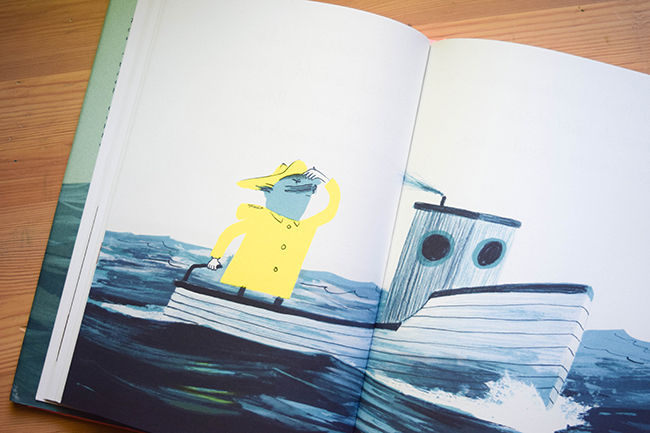

Still not satisfied, Fausto conquers a boat and heads off to sea, determined to make it his as well. But, when it comes to the sea, Fausto is in just a little too deep. It fights back.

“But you do not even love me,” the sea tells him, refusing to be his.

When Fausto lies and tells the sea what it wants to hear, the sea doesn’t buy it.

“How can you love me when you do not understand me?” the sea asks him.

Fausto continues to be demanding, acting as if the sea is owed to him. He promises to stomp his foot and show it who is boss. But the sea is right. Fausto doesn’t understand it. When he climbs overboard to show the sea who is in charge, he disappears into it, unable to swim.

While sad for him, the sea and the mountain and everything else Fausto had made “his” go on — “for the fate of Fausto did not matter to them.”

When I reached the end of the story the first time, I was really struck by its darkness. Not many picture books end with the death of a character, although it’s not unheard of. Jon Klassen’s beloved I Want My Hat Back is just one (hilarious) example. And fables are often dark. Two of the three little pigs are gobbled up. King Midas turns his daughter to gold. The wolf in sheep’s clothing was killed by the shepherd. Why wouldn’t Fausto meet an equally dark end?

The themes running through the story are also heavy. Greed, selfishness, self-destruction. A tyrannical, self-absorbed, entitled leader. Humanity’s attempt to have dominion over nature and nature’s raw power. And, as Publishers Weekly put it, “the merits of calm refusal in the face of dangerous individuals.”

Deeply layered and incredibly complex, the illustrations and layout make the book seem anything but. Simple and muted with bursts of neon pink and yellow, the book is very slowly paced. Large areas of white space (one spread only has a single word: “Eventually,”) force you to drink it in slowly, watching carefully as Fausto throws tantrums and makes outrageous demands with wild, angry scribbles above his head. He seems even more ridiculous when you watch him so slowly and carefully.

Maybe because of the illustrations or perhaps more closely tied to life experience, the moral of the story seemed much simpler to my daughter.

“He’s a bully,” she said in her most matter-of-fact voice. “The story is about why you shouldn’t be a bully.”

A bully for sure, Fausto’s tale is one that will stick with you even after his story is over.