How We Talk (or Don’t Talk) About Diversity When We Read with

Our Kids

by Matt de la Peña

I still remember the concerned look on my mom’s face as we stood together in the doll aisle at Toys “R” Us. “What am I supposed to do now?” she said under her breath.

I shrugged.

I was just a freshman in high school, and I didn’t want to be there. But before my mom would drop me off at the gym, so I could play ball with the fellas, I had to accompany her to the toy store to help pick out a gift for my youngest sister.

It’s important to note that my working class folks didn’t have a whole lot of disposable income when I was a kid. We’d wake up most Christmas mornings to find one wrapped gift each tucked under the tree. Some years it was socks. Other years — the good years! — it was a plastic skateboard, or a Barbie Corvette, or an Easy Bake Oven. That year my sis happened to be obsessed with Cabbage Patch Kids. Which were expensive. And hard to find. But my mom was determined to make it happen. She called stores all around the city until she found the one place that still had them in stock.

The problem?

By the time we got to Toys “R” Us, they only had three left. And none of them looked like my sis.

We’re mixed kids. Half Mexican, half white. Back then you never found “mixed” dolls, so my mom would opt for the “Latino” doll, or, more commonly, the white doll. But here she was, staring down at three African American Cabbage Patch Kids.

After another minute of hemming and hawing she lifted one of the black dolls off the rack, paid for it with credit, wrapped it in shiny candy cane paper, and tucked it under the tree between the gift for me and the gift for my middle sister. When my youngest sis tore open her present that Christmas morning she jumped up and down and spun around in circles clutching her very own Cabbage Patch Kid tightly against her chest, chanting, “Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you!”

There weren’t any deep, race-related discussions that Christmas morning. My mom didn’t sit my sis down and use it as some kind of teachable moment. It was simpler than that. It was just an excited little girl and her new doll.

As a new parent (I have a 10-month-old baby girl!) I’ve recently discovered a fascinating phenomenon. Whenever my daughter falls and bumps her head, or coughs up a mouthful of sweet potato, she looks to me or my wife before reacting. If we remain calm, she remains calm (most of the time). Conversely, if we freak out, she freaks out.

Lately I’ve been wondering if this phenomenon holds true in other contexts as well. Like with dolls. Or making new friends at the park. Or . . . literature.

Maybe kids look to us (parents, teachers, librarians) before deciding how to frame a new book they’ve just encountered. If we make a big deal about the differences between the young reader and the characters in the story, isn’t the story more likely to be viewed as “other” in the child’s mind? If we focus on the narrative instead, and on the journey of the characters, maybe a young reader’s attention will remain here, too. At least in the short term.

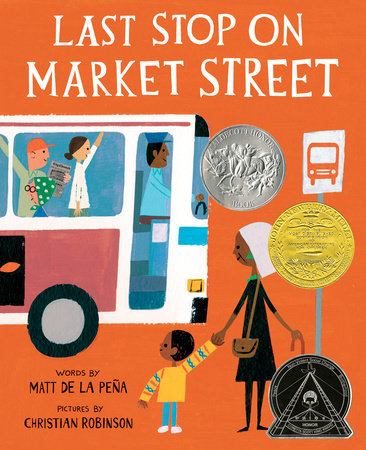

This is my current approach to writing. I still strive to write books featuring diverse characters, but I now try to place them in stories that have nothing to do with diversity, not overtly anyway. Last Stop on Market Street is an example of this new approach. CJ and his grandma are African American, but the story is about a colorful bus ride through a bustling city. It’s about a boy’s relationship with his amazing grandma. It’s about seeing the beautiful in the world and the power of service. My dream is for the book to be read by (and read to) kids of all races. I didn’t set out to write a book that would spark race-related conversation; I wanted to take readers on a fun ride with two special characters.

Don’t get me wrong, my little sis did eventually ask my mom about the skin color of her Cabbage Patch Kid. It was almost a year later. By then the doll was my sister’s best friend. The point is, my sister arrived at her questions on her own. Some readers of Last Stop may eventually ask questions, too. In no way am I saying these conversations should be avoided. I’m saying these conversations don’t have to be the focus. I’m saying it’s worth considering how we consciously or unconsciously frame “diverse” stories to the little guys.