The Importance of Latinx Representation in Children’s Literature

by Pablo Cartaya

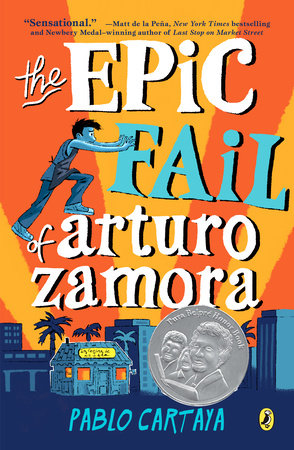

I recently recorded the Spanish language audiobook for my novel, The Epic Fail of Arturo Zamora, and, to be perfectly honest, it was terrifying.

It wasn’t because I was afraid of getting into the recording studio. I was cool with that. Having recorded all of my books into audiobooks (even getting an Audie Award Finalist honor), I wasn’t scared of the studio experience. What truly scared me was something deeper – it was a type of imposter syndrome tied to an aspect of Latinx identity – speaking Spanish.

An article Kevin Garcia wrote for NPR’s Code Switch helped me understand what I was feeling. He writes, “[T]he gentle (and not-so-gentle) teasing from family and friends for mixing up ser and estar; the uncomfortable silence that fell between my cousins and me, neither of us able to communicate during my family’s trips to Mexico.”

My first language was Spanish. I didn’t learn English until I was five – when I started kindergarten. My teacher called me Paul and reminded me that I should speak English in school. Dismissing my name and language as something not acceptable essentially erased a piece of my story for much of my childhood. And so, two decades later, faced with the task of recording my book in the language of my Cuban heritage, I nearly panicked. Because failing, or sounding awful, was the ultimate betrayal of what made me truly Cuban American – the ability to communicate in the language of my abuelos.

I’ve always been proud of my Cuban heritage. The complicated history that brought my parents and grandparents to the United States has fascinated me my entire life. My books all carry a deep personal history that is inextricably tied to my Cuban identity.

I wrote The Epic Fail of Arturo Zamora, and really all of my books, with a good dose of Spanish infused throughout the text. I wrote them this way in spite of my bilingual limitations. I wrote them because I needed to. I needed to have stories that represented the kid I was growing up. A kid who adores his abuelos, loves his family, struggles with Spanish, and who is constantly searching for ways to better understand more about his cultural identity. I write these stories to understand myself. And in the process of doing so, maybe, just maybe, there is a kid out there who will see themselves also. A kid who will read the pages of my stories and say, ‘I understand that,’ ‘I get that,’ ‘that’s my life!’

The importance of Latinx representation in children’s literature cannot be overstated. But I also want to add, Latinx representation in publishing needs to become a priority as well. We need Latinx people of all backgrounds and experiences, in all levels of publishing. We need them to have real power to make decisions that represent the books people like me write. That’s when representation will start to make real progress. Publish our books, yes. But also hire our people to represent those books.

The Latinx story is not a monolithic one. It is varied and nuanced. It’s crucial to have editors, publicists, publishers, and yes, authors representing the breadth of the Latinx experience. There’s something beautiful about our shared experiences. Many of us are Cuban, Ecuadoran, Puerto Rican, Mexican, Peruvian, Haitian, Brazilian, and every over Latinx-centric country on earth. I love connecting with mi gente. I love reading their books, talking them up, and laughing it up with them. Our stories are slowly making their way into classrooms — and that’s a good thing. But there’s work still to be done.

I, for one, am here for it. The whole journey.

After some introspection, I was able to overcome the feeling that I somehow didn’t belong in the studio recording my book in Spanish. I needed to push myself. To feel like I could reclaim a part of my identity that was lost. I remembered something former U.S. Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera said: “I want our young Latinos and Latinas to write their hearts out and express their hearts out and let us all listen to each other.”

Our stories are so individual and unique, and yet, there is a common humanity about them. This is the gift authors and publishers can give children who claim the myriad of experiences that define the Latinx experience. It’s our way to tell them they are not alone.

The world of children’s literature is infinitely more colorful with our voices and stories in them. And we’ll keep writing them without compromise to our identities. Like the song goes, no pare sigue sigue…