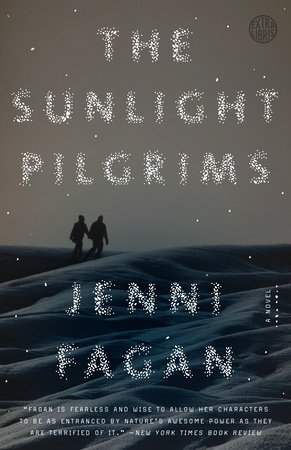

We Are All Made of Stars:

Jenni Fagan on Letting Kids,

and Characters, Be Themselves

by Jenni Fagan

I write characters who challenge me. My characters are complex because people are complex, and it is simply more interesting to spend time with someone who struggles, as we all do, with the experience of existence. It’s my job as a writer to allow my characters to become themselves — extraordinary, strange, dangerous, mundane, courageous, idiotic, awful, brilliant, flawed, and compelling — not for me to impose myself all over them. If I walk in there at the start and carve out rules, I just cut off my character’s potential before it even gets a chance to take root.

After writing several novels, I’ve realized that it takes time to get to know our characters. They rarely turn up wholly formed. They change as life does. They grow and alter. When you think a character will be a piccolo player, you’ll find out they can barely hit out a basic beat on a drum. You have to be patient and allow them to reveal who they are as things happen in their lives. How they react, behave, feel, speak, or dream — all those things begin to create a character who is whole and of themselves. While there are parts of me in my characters — common obsessions, common fears — a character is more than an extension myself, the author.

When Stella turned up in early drafts of The Sunlight Pilgrims I could see her goth sensibility, striped tights, and different colored nails with glitter on them. I was hugely drawn to her witty one-liners, her BMX bike with a pirate flag on the back, and the complicated relationship she had with her mother. But I knew right away there was something I wasn’t “getting” about Stella. I’d had a similar experience when I was writing my debut novel; it took me a whole draft to realize my protagonist did not want to speak in straight English, and she didn’t want to be written about in the third person either. Once I realized that, she came alive on the page.

I had to tread softly around Stella to work out what I was missing, what I wasn’t hearing. I soon remembered that Stella had not started out biologically female. In between drafts and living my real life, I had somehow lost that detail, but it was obviously the key to understanding who Stella really was. As soon as I worked that out she made complete sense to me. Of course, I felt a responsibility to get this part of her journey right. I had grown up among the LGBTQ community through my teens and 20s so it didn’t seem that huge a leap in some ways, but I recognized the need for research. I wrote to Kate Bornstein (author of Gender Outlaws, a book I highly recommend), met lots of great writers in the transgender community, and read loads of great books. These were all great starting points and were the very least I could do for Stella along the way.

I discovered that Stella and I had some things in common. As a young person, I also grew up being judged for circumstances beyond my control. I was raised in the foster care system so I understood what it meant to experience prejudice and also be unsafe in many communities. Children in foster care face challenges that are largely unseen by people outside the foster care system. They are often considered suspicious just by their presence. They experience more violence, and are less able to access higher education and enter the workplace with ease. They’re given negative messages about who they are by the institutions around them, all because they were born to circumstances they did not choose.

My heart went out to Stella when I saw how much she wanted to be accepted by her local community, her family, her previous friends. I related to that most humane instinct to find a safe space; it is so awful to be denied that at such a young age because of other people’s ignorance or fear.

I also had the privilege of getting to know Stella’s humor, her wisecracks, her soul, the struggles she has with her mother, and how she deals with her identity as a young trans woman. There is a part in The Sunlight Pilgrims when she realizes that there is no “right way” to be trans, no right way to be human — she realizes that girls are often preconditioned to be “likeable,” to not “shake the tree,” and that these constrictions are toxic and undermine happiness. I felt for her struggle to be a “good girl,” to be liked, to just hope that someone might “want her” one day.

Stella Fairbairn is a trans teenager, but I knew from that start it would not be what defines her entirety. She is the fastest kid on a sledge. She has guts. She is moral. She is fiercely funny. Stella is sensitive and quiet, and sometimes loud and awkward. She has an open heart and the courage to let it beat truly in a world that does not always seem to have a place for her. She is a good friend to Dylan when he arrives and, as time passes, she learns to embrace her unconventional mother and family.

I often thought about my own child when I was writing Stella. I have a little boy who sometimes wanted to paint his nails or try on make-up, and who was also equally happy surrounded by LEGO and cars. I wanted to raise him to feel like it doesn’t matter how gender is meant to limit individuals’ interests or happiness.

I am often told I write in a very “male” voice. I have been told I am very driven in a masculine way, that I am unconventional as a woman. And I have no idea what other people mean by any of it.

I am only myself. As is Stella. As are all of us.

Gender and beauty and talent and courage should hold no threat in their extraordinary plurality. All of these variations are perhaps just part of the fact that human beings originated from the carbon matter of stars, and each of us has a little of that sparkle of original stardust inside us. We are all meant to be here, children of the stars. Who are any of us to question that?