Why the Theme of My First Novel Is Childhood Loneliness

by K.G. Campbell

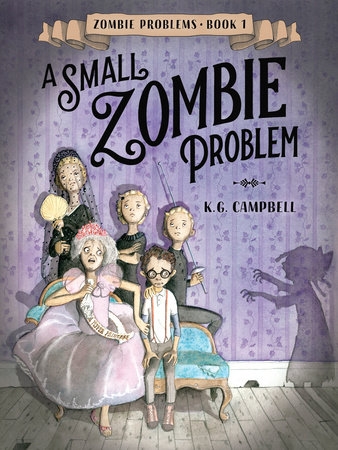

The undead. Necromancy. Ominous swamps. Immense white alligators. My first novel, A Small Zombie Problem, is a darkly humorous mystery, jam-packed with eccentric characters, sinister motives, and spine-tingling page-turners.

And yet, if you asked me to select one illustration that best captures the heart of this story, it wouldn’t be one that reflects the passages of dramatic action or creepy suspense that fill the pages. It would be the quiet, seemingly insignificant image that accompanies this essay.

“I’m lonely, Aunt Hydrangea,” said August simply.

With primary influences such as Edward Gorey, Tim Burton, and Neil Gaiman, it’s hardly surprising that my debut novel should feature a zombie in the title. But to a large extent, the walking dead, the crumbling mansions, and the gloomy corners of Southern Gothic are merely pretty packaging. Whatever look-at-me subject matter I chose to wrap it in, my first foray into middle grade fiction was always destined to be about childhood loneliness at its heart.

I was 4 when I attended the first birthday party I can recall. My arrival at that event numbers among my earliest memories, suggesting that it left a big impression. And I can tell you why: I was terrified! Other children, I discovered to my horror, were loud and violent and utterly dreadful. And thus began a lifelong struggle with social interaction.

I simply did not fit. The other boys were too physical. The girls were too bossy. All the kids seemed to shriek and yell and barrel through the world with abandon. Like animals! By some random spin of nature’s wheel, I had arrived here ill-equipped to connect with my peers. So, I retreated. Adults began to refer to me as “shy.” “Sensitive.” A “lonely only.”

In this enlightened age of empathy and inclusion, we are encouraged to embrace — to celebrate — our individuality and uniqueness. And indeed, I do own my introversion now. I no longer regard it as problematic. Alone time is not only desirable but necessary to my kind.

But there’s a big difference between alone time and loneliness. In our grown-up sophistication, we might imbue the latter with a certain romantic melancholy: “a lonesome watering hole,” “a lovely, lonely princess.” But loneliness by its very definition is a negative state. An antisocial hermit who rejects all human contact is not lonely. A child who longs to belong is.

As a youngster, I would observe the interaction of siblings or friends with both an aching sense of yearning and a level of dread that proved to be an insurmountable obstacle. Imagine longing to enter the cozy, busy tavern beyond the window while stubbornly refusing to quit the tranquil solitude of the foggy street. Childhood loneliness can be a complicated matter.

August DuPont, A Small Zombie Problem’s protagonist, experiences crushing loneliness as the result of situational rather than psychological factors — a simpler, more tangible premise. But I hope my presentation of his predicament conveys some of the sadness that lingers around any lonely child, a sadness they will likely not identify until later, in retrospect.

I poured all of this into the above image. Many will miss it for its subtly. Publishers prefer us to capture emotion with facial expression; it’s more direct and satisfying for the audience. But occasionally I choose to dial up the poignancy of a moment by harnessing body language. Applied sparingly, it can be incredibly powerful in a cinematic way.

I used it for the reunion of the heroine and her squirrel in Kate DiCamillo’s Flora and Ulysses. The protagonists’ faces are entirely concealed, but Flora’s knees have buckled, and she has slumped to the floor. Ulysses clings to the girl’s hoodie as if he will never let go. No expressions, yet the reader sees everything they need to know and feels everything they’re meant to feel.

Here, Aunt Hydrangea’s neck bows with sorrow as she is brutally confronted by her nephew’s misery. Her shoulders slump with guilt as the child in her protection quietly demands release from the solitude she has imposed upon him. This image is filled with emotions too complex to rely on facial expression alone; it’s an ode to a lonely childhood.

Like so many others, reading was a lifeline for me, particularly between the ages of 8 and 16. The worlds and characters created by Enid Blyton, Roald Dahl, Alan Garner (yes, I grew up in the UK), filled a gaping void. Entrenched in a blanket-fort with my dog and a family-size bag of potato chips, I was in heaven. Not a sign of loneliness or sadness in there.

And like so many others, it was my voracious appetite for reading books as a kid that led me to pursue writing them as an adult. I could — perhaps should — tell you that I selected the theme of my first novel in an act of benevolence, an attempt to throw the same lifeline to another blanket-fort dweller sheltering from the raging storm of childhood. After all, coming across someone just like yourself, even a fictional someone like August DuPont, can make the loneliness seem less lonely.

Such a claim wouldn’t be entirely untrue. Of course, I want my books to spread joy. Of course, I hope they might be of some small benefit to someone. But perhaps my motivation in selecting its theme lay a little more in my desire for A Small Zombie Problem to be, quite simply, good. To be authentic. To have heart.

And if you want authenticity, if you want tangible, relatable heart, you know what they say: write what you know.