Fanning the Flame of Storytelling

by Malia Maunakea

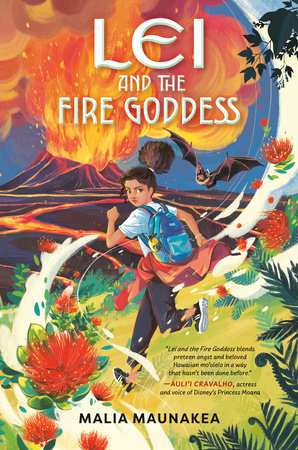

When I set out to write what would become Lei and the Fire Goddess, my middle grade Hawaiian contemporary fantasy set in the lush rainforest on the Island of Hawaiʻi, I wanted to write a fun adventure about a hapa-haole girl whose best friend gets kidnapped by a fire goddess when she doesn’t take her tūtū’s stories seriously. I looked at Rick Riordan and how he propelled Greek mythology into the hearts and minds of young readers around the world, and thought to myself, “How cool would it be if everyone knew about our Hawaiian legends too?” Answer: Really cool, but also really scary. The great thing about Greek mythology is that it has been written about over the centuries by hundreds of authors, all with their own ideas of how to portray the gods and goddesses. What is terrifying to me is that this could be the only book on Hawaiian mythology that some children read.

And we aren’t a monolith.

Before I get into the impact of being one of a few writers in the middle grade Hawaiian cultural space, I would like to clarify an important nuance of the definition of moʻolelo, or stories. According to wehewehe.org, moʻolelo means both fable and history, myth and meeting minutes. In Hawaiʻi, our realities and legends are intertwined and a part of our genealogies. People can trace their family lines back to these stories, and they play a role in today’s culture. Writing about these heroes is a kuleana (privileged responsibility) that must be done with great care and respect.

Growing up, I heard about Maui, Pele, and Poliʻahu’s many feats and adventures. There were songs and chants about these great Hawaiian deities, and I learned hula in their honor. In early elementary, there were picture books of these tales in my classrooms with brightly colored illustrations that fueled my imagination about why the sun crawls across the sky and where fire comes from. But by the time I reached fourth grade, I struggled to find age-appropriate books about them and turned to reading about blond-haired, blue-green-eyed twins with lives as foreign to mine as the ones in movies and television. I never stopped to wonder why there weren’t books set in Hawaiʻi. Instead, I accepted that books were windows into a different world.

RELATED: Start Reading an Excerpt of Lei and the Fire Goddess

With my children growing up in Colorado, I longed to give them a glimpse back into our Hawaiian values, lifestyles, and traditions. Still, my reverence toward the histories weighed heavily on me when I considered the lens through which I wanted this story told. I knew I wanted to start with Pele, since my earliest memories were of growing up in her backyard in Volcano, her eruptions filling the skies. But the question of how to write about a goddess who is still very much present and is also people’s genealogical kupuna (ancestor) gave me pause.

I weighed the pros and cons. The possibility of creating something that could excite the next generation of readers and give my kids a chance to see themselves in a book versus the fear of upsetting folks in some way. Ultimately, I decided to create this story and see if there could be space on the global shelf for moʻolelo of kids like me.

Figuring out I wanted to write it was one thing. Learning how to write it and what to do next was totally different. I am not the author who was told their whole life that they’re so creative and their stories are great. No, I was told I’m good at math and science and that I should look into a job in engineering. So, after the engineering degree and decidedly un-writerly career, I was ready for something new and asked myself what I wanted to do with my life. I dug deep and discovered a tiny, long-ago glow for the joy of storytelling. And once I brought it back to a roaring inferno, none of my education prepared me for what to do with the fire.

So, I did what my education did prepare me for: I researched. I learned about writing groups, learned the language of CPs, betas, queries, and sub. I started taking papa ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language classes) since most of the stories from the Hawaiian perspective are written in that language. I’ve learned enough to navigate some of the old newspapers to find a particular oli, a Hawaiian chant used for storytelling. The joy I felt when I successfully navigated through the pages to find that chant was incredible. It’s like a backward treasure chest: the riches are right there. I just need to learn how to read the map to return home.

My goal was originally to share our moʻolelo, to help my kids and others see themselves reflected in a book, not just looking through the windows of someone else’s adventure. Now that Lei and the Fire Goddess has found its home on bookshelves this summer, I want to fan the flame of possibility in other writers. Let’s get more of our stories heard. Let’s have entire bookshelves filled with our moʻolelo so the stories live on and the next generation can see how beautifully different our voices can be. With every new book that comes out from a Kānaka author, a bit of our tradition is carried on, giving the next generation access to insights of those who came before, a guide back to a place or time that at first read might seem unfamiliar, but eventually will feel like coming home. That way, none of us need to be scared of shouldering the kuleana of representation for our entire culture.

-

Get the Book: