Author of Born Behind Bars on Reading Beyond Your Own Experiences

by Padma Venkatraman

Recently, I heard from an educator, who said she loved Born Behind Bars. But, she added, “that never happens to kids in my community.”

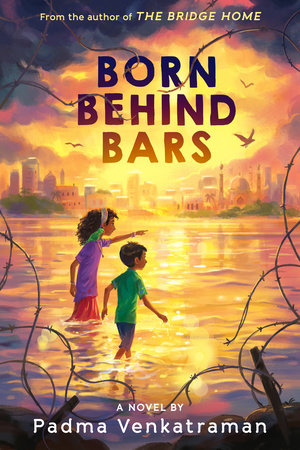

Born Behind Bars is inspired by a true story, and it’s set in India. It’s about a boy who lives in jail, is turned out on his own when he’s nine years old, and refuses to give up the hope that he can somehow free his innocent mother, who remains behind bars.

I assume the educator meant that young people in her town don’t grow up in jail. Well, few of us do. But given that about 5 million children in our country have at some time had an incarcerated parent, surely, we’ve all likely interacted with someone to whom incarceration is part of life, whether we’re aware of their situation or not.

Some books are doors that transport us to a different time or place – others also transform us by allowing us to briefly identify, from within a character’s experience, with someone else’s life and views. Books invite us to engage in an exercise in empathy – and this, alone, is enough reason to include a book like Born Behind Bars in a library, whether others in the community have similar experiences to the protagonist or not.

Second, the theme of wrongful incarceration is vital to acknowledge and discuss – not only as it occurs in India, where Born Behind Bars takes place, but also in terms of the parallels in our own society. More than half the innocent people on death row are Black, and even after exoneration they often wait years longer for release than white people; innocent Blacks are 12 times more likely to be convicted for drug crimes than innocent whites. If any community is unaware of or feels removed from these horrifying facts about wrongful incarceration, they must be exposed to them if they want to rid our society of injustice.

Readers will surely differ in how they approach any important issue, including this one; and that’s fine. Books like Born Behind Bars allow readers to engage in introspection, to confront and question deeply held beliefs and assumptions, and provide an invitation for them to enter into mutually respectful discussions.

Finally, and perhaps most astounding of all, is the educator’s belief that a book doesn’t deserve to be included if it broadens a reader’s experience. One of the most amazing things that books can do – especially during this pandemic – is expand our world!

The problem, of course, is that the complaint more than just absurd. I’m betting, for example, that while few teachers question whether a modern reader will be able to relate to the white British girl in The Secret Garden who moves to a manor house after leaving India where her parents died in an epidemic, they might have reservations about whether the modern reader can relate to the indigenous protagonist of The Birchbark House. Unfortunately, in my experience, the accusation that a book is intrinsically unrelatable to readers because of its content is usually leveled at diverse books.

Recently, a reader said Born Behind Bars was “The One and Only Ivan meets Bud, Not Buddy.” After I got over my joy at receiving this high compliment, I remembered hearing author Ellen Oh remark that adults rarely seem to worry about whether a talking animal is relatable. And, I’m pretty sure none of the kids in that educator’s community have flown on brooms but that doesn’t seem to make educators worry about the relatability of the Harry Potter series. In spite of all that’s been said, over and over again, about the importance of stories written by and with protagonists from historically underrepresented and marginalized groups, fears that these stories are “unrelatable” remain.

Who wants to read only about things they’ve experienced, over and over? Perhaps some. But I’m guessing most readers prefer a book that takes them on adventures of the mind and heart. Excluding a book because of its international setting or unusual theme or the protagonist’s diverse background is, at best, limiting a young person’s opportunity.

At worst, it’s continuing to suppress historically marginalized and underrepresented voices and stories – and helping to maintain the status quo, if not actively promoting racist hate.

-

Get the Book: