The Page-Turning Allure of the British Upper Class

by M. A. Bennett

It’s often said that Americans are fascinated by British culture. The Harry Potter books, the most successful children’s series of all time, are essentially about a British boarding school. TV series like “Downton Abbey” and other period dramas plundered from the pages of Austen and Dickens have become smash hits. As for the Royal Family, they need only sneeze to make the front pages.

Born in England myself, I was close enough to the upper class to look in firsthand. My grandmother Ina Hoggarth worked at Langcliffe Hall, a stately home in the north of England. She went there as a kitchen maid at the age of 14 and worked her way up to housekeeper in the years approaching the Second World War. The Hall was owned by Geoffrey Dawson, editor of the Times newspaper. When I was born, my mother worked full-time, so I was raised by my grandmother in the housekeeper’s cottage. Living on the grounds of a great house, I saw up-close the upper classes at play. The Hall had a grouse moor, and the family often hosted shooting parties during the season. My grandmother would work all weekend and come home on Sunday, dog-tired, with stories of the weekend’s sport. The gamekeeper, improbably named Perfect, would bring us a brace of pheasants for our Sunday dinner, still warm, floppy-necked, and riddled with shot.

Of course, while I was growing up in the housekeeper’s cottage and attending the local comprehensive school, the sons in the big house were living a very different life. As a teenager, I would see them in the village pub during the holidays, but during term time they were at Ampleforth College, an exclusive boarding school in North Yorkshire run by Benedictine monks.

Thanks to my excellent teachers, I was given, by some miracle, the same chances as those boys. I went first to Durham University, a stunning collection of ancient colleges, one of which was, unbelievably, a castle. Then, when I was awarded a British Academy scholarship, I won a place at the prestigious St. Peter’s College, Oxford — something unheard of for a housekeeper’s granddaughter. At Oxford, I felt that I’d landed on Mars. Suddenly everything I’d read about in Brideshead Revisited was happening to me. I went punting on the Cherwell on lazy summer afternoons. I stayed up all night to see in the May, and climbed the tower of Magdalen College while the May Day bells rocked the stone. I studied in the ancient, dusty silence of Duke Humfrey’s library in the Bodleian. I watched the rowing in Eights Week. I found the low door in the wall of Trinity College Gardens that was supposed to have inspired Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. I even drank in the “Baby and Bird,” the famous Eagle and Child pub, where the Inklings, a group of friends and writers including J.R.R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, once gathered.

And of course, suddenly, I was in the company of the boys (and girls) from the very estate where my grandmother worked. They would be sitting next to me in the library, in the pub, in the great hall at dinner. These were kids who would go home during the holidays to houses at least as big as Langcliffe Hall. These were the kids who went skiing every winter (I’d never been on skis in my life). These were the kids who’d had a gap year after school, and spent it teaching in Africa or South America, coming back with a henna tattoo or an extra earring or a beaded plait of hair, to be erased or removed or cut off respectively before graduation, when they would begin work at their fathers’ investment banks.

These kids were uniformly lovely to me. Whatever might have been said about my gauche manners or my accent behind my back, I encountered no unpleasantness at all to my face. The upper classes would never be so impolite. Their armor is manners; their great weapon is charm. After university, my marriage to film director Sacha Bennett, and the beginnings of my writing career, my relationship with the family at Langcliffe Hall underwent another interesting evolution. The lady of the house was an aspiring writer, and I would go to the Hall and we’d talk about publishing. Her eldest son, a talented art director, ended up working on two of my husband’s films. Sacha and I went to tea, for drinks, for dinner. Our kids rode the Hall ponies. We were even invited one year for New Year’s Eve, a social leap my grandmother would not have dreamed of. And even then, when I walked not through the tradesmen’s entrance, but through the front door, as a published author with her film director husband, I still felt a little, well, wrong. I spent the evening standing, holding a glass of champagne, on the tiger skin rug I used to play on as a child while my grandmother cleaned it. You may think that after everything I experienced in my life I would no longer feel like a fish out of water.

But you’d be wrong.

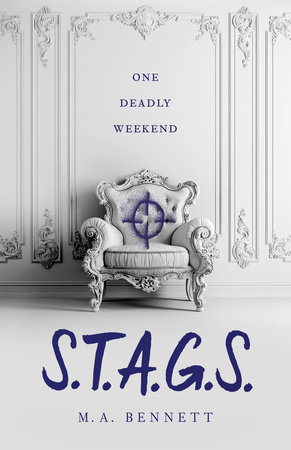

My young adult novel S.T.A.G.S. is about an ordinary girl who wins a scholarship to an exclusive English boarding school, St. Aidan the Great, and is then invited by the richest clique in school to spend a country house weekend at Longcross Hall, where the promised traditional blood sports — huntin’ shootin’ fishin’— take a dark turn. It is a more personal project than I intended, as the book is inspired by my own experiences.

So yes, maybe I’ll always feel like I’m on the outside looking in.

But maybe that’s what keeps the fascination alive.