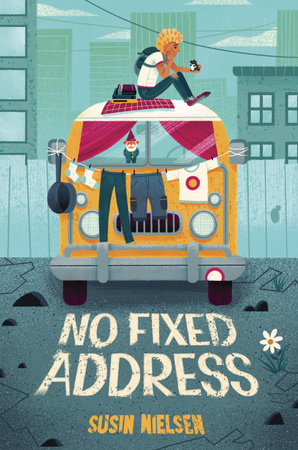

Why I Wrote a Middle Grade Novel About a Child Without a Home

by Susin Nielsen

Ideas percolate to the surface in the oddest moments. In this case, I was half-asleep in a hotel room in early 2015 when the thought drifted through my mind: “I could write about a boy who lives in a van with his mom.” If I try to trace it back, I suspect this initial notion came from a conversation I’d had years earlier with a couple who’d lived in a van with their 8-year-old daughter for a year while the father went to university in Vancouver. They described it as a great adventure, but a small (and, yes, judgmental) part of me wondered if it had always been an adventure for their daughter, especially in the cold, rainy winter months.

When I began setting pen to paper, there was already a housing crisis in Vancouver, Canada, where my novel No Fixed Address is set. But I had no idea just how “of the moment” the story would be by its publication date in 2018. Things have gotten much worse. Homes are increasingly treated as investments, a place for the wealthy to park their money. Housing prices have skyrocketed. Rental units are scarce and costly, and renters are constantly being evicted as older homes are sold and torn down, replaced by large homes that — to add insult to injury — often stand empty. More and more of our hardworking citizens are being pushed out, or pushed to the brink of poverty and despair. The lack of political action at every level is disheartening.

And of course, none of this is a problem that is unique to Vancouver. It’s happening all over North America — sadly, it’s a rather universal theme.

In my own city, and in the past year in particular, I’ve begun to notice a lot of camper vans down by the beach. And not just parked there, but lived in year-round. There have even been articles in our local paper about this new phenomenon. Whenever I spot a VW Westfalia that’s clearly being inhabited, I find myself wondering if the door will open and Felix and Astrid will step out.

All of this said, when I started writing the book, I didn’t think, “I’m going to tackle the issue of homelessness.” I never start with an issue; I start with a character. I told Felix’s story, and that wound up illustrating how easily regular, everyday people can edge to the precipice of homelessness — what a slippery slope it can be from having a roof over one’s head to being out on the street. I wanted Felix’s experiences to feel very real yet never be too dark or heavy; humor is very important to me in my novels. I also wanted to write a complex mother, who is maddening, frustrating, but also extremely loving. I think many of us know someone like her. Part of Felix’s journey in No Fixed Address is also the dawning realization that his parent is fallible, and flawed — something every kid goes through at some point.

My novels have a moral core, but they don’t moralize. I hope that my readers will come away with a sense of empathy for the many children who find themselves in situations similar to Felix; they are no different from those of us who are fortunate enough to have a roof over our heads. No child should be without a place to call home. Housing should be a basic human right for all.

-

Get the Book: