Helping Kids Think Like Writers:

A Talk with Frindle Author

Andrew Clements

by Kathryn Haydon

Children’s book author Andrew Clements has dozens of titles to his name, from picture books to novels to early reader chapter books. His most well-known work is Frindle, a story about the power of language, invention, and the push-and-pull between a creative student and a no-nonsense teacher.

Andrew writes in his home office surrounded by books, many of them mainstays from his childhood. “They stay with you all your life,” he says as he rattles off some of his favorites: Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White, The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame, The Story of Thomas Alva Edison by Enid LaMonte Meadowcroft, and Tom Swift and His Flying Lab by Victor Appleton II.

I talked with Andrew about his inspirations, his new and upcoming books, and his writing advice for kids and parents.

What was the catalyst that caused you to write your first children’s book?

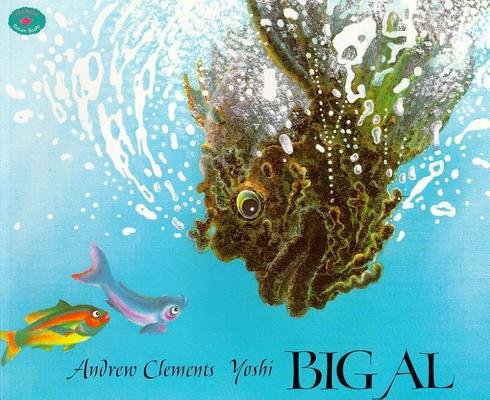

Early in my career I worked for Picture Book Studio as a copyeditor, writing advertising copy and leading the sales team. One day I was asked to write the text for an under-the-sea themed book to be illustrated by the Japanese-American artist Yoshi. This book became Big Al, which was a success from the start and even won an award from the United Nations.

After that I wrote seven more picture books that were published. One that was not published was called Nick’s New Word, and that became Frindle after several editors said it needed to be a chapter book, not just a picture book. I was glad those editors gave me such good advice. Once Frindle was published in 1996, I was on the way toward having writing become my full-time job.

Before you became a full-time writer, you were a teacher and a singer-songwriter and you worked in book publishing. How did this circuitous career track help enrich your writing, and how does it still influence your work today?

Writing fiction is the artistic reprocessing of experience. The more a writer experiences, the more raw material he or she has to draw upon. With time, one can come to think more clearly about character and hopefully develop compassion for oneself and others. I learned just what I needed to learn from each experience and this has fed into my books.

What would you tell kids about finding their own raw material?

My best advice for any aspiring writer is to read. Reading good writing, with awareness about what makes it good, will help teach you about writing. Writers often find the motivation to write when they are stirred by what they read. They start thinking like a writer.

How do you describe “thinking like a writer” to a kid?

If you are thinking like a writer, you know that all around you all the time there is story potential. When you see somebody walking down the street, you look at that person and part of you wonders, “What’s his story? What does the look on his face mean?” and you start spinning it out. One moment of observation or a snippet of conversation will make demands on you. It will press you to figure out how to find the words to make somebody else experience the story you have glimpsed.

Once someone starts thinking like a writer and takes the time to actually write, how can they improve their craft over time?

Small adjustments can make writing that is just okay into writing that is really good. Years ago, I visited a fifth-grade classroom in New Hampshire where the teacher had gotten the kids excited about the iterative process of writing. They understood the importance of making small changes and creating several drafts. If you dedicate time to it, you can get your use of words to rise to the level of art.

The Map Trap came out in paperback this summer. I love how you incorporate varied interests that kids have into your work — interest in language for Frindle, interest in numbers for A Million Dots, interest in dogs and poetry in Dogku, and interest in maps for this one. Do you do this intentionally?

Yes. Good writing doesn’t happen unless it’s done on purpose. The trick is to write with clear intent, but to keep a story from feeling purposeful or didactic. The Map Trap is a pretty simple story about a kid who is crazy about maps and starts making maps of things like his social studies teacher’s brain, based on what she talks about. (She is worried about her hair a lot!) He has a whole portfolio of these map-based observations of people that he never shows to anyone, but one day it goes missing and he’s terrified he is going to get in trouble.

Most of my novels are set in and around school because school is such a big part of life. I try to keep it fresh and varied, drawing on different interests and different types of thinkers, but revolving around school — which is one of those infinite topics.

Which of your newest books do you think kids would love to pick up?

The paperback boxed set of my history/mystery series Benjamin Pratt & the Keepers of the School is coming out on November 15! One of my favorite things to do is to visit old buildings and rummage around until I find things. The plot for this series was inspired by an 1862 Indian Head penny that I found tucked under a piece of board. It could have rolled there, but what if somebody had left it there on purpose? This series weaves American history with hidden clues, kid sleuths, and, of course, old buildings.

What book can we look forward to next?

In Fall 2017 you will get to read The Loser’s Club with a main character who loves books to the point where it creates problems for him. The story is the process of him realizing that books can enrich your life, but when they try to become your whole life, you need to regain your balance. Part of the inspiration was drawn from an observed moment when one of my sons received a book as a gift, plopped right down in the middle of his own birthday party, and got lost in the story, oblivious to the other children playing around him!

From your experience as a teacher and a parent, how do you suggest adults support kids’ own unique interests and expressions of creativity?

My first year as a teacher, I was assigned a challenging group of 30 fourth graders. I came to the conclusion that many were really smart and artistic and needed a lot of fresh and interesting things to do. Near the end of the year we created a huge geodesic dome from large triangles made from cardboard bicycle boxes according to Buckminster Fuller’s formula. Everyone in the classroom was given one triangle. I said, “Everybody gets to decorate at least one of these. The only rule is that your panel has to teach something, but it can be anything you want, any subject.” The work we got was amazing.

This experience taught me that if you want kids to be creative they need the opportunity to be creative. Unfortunately, in many schools today there is no time for real creative thinking, but unstructured time is good! Kids need time to sit and read, build forts, play in the dirt, listen to music, and to write. Adults can encourage this by example, and by helping kids discover what they’re really interested in. And then we need to give them the time and resources to pursue these interests.

What is your favorite book by Andrew Clements?

-

Books by Andrew Clements:

-

The Map Trap

Preorder from:No Talking

Preorder from: -

Things Not Seen

Also available from:A Million Dots

Preorder from:

Andrew Clements is the author of the enormously popular Frindle. More than 10 million copies of his books have been sold, and he has been nominated for a multitude of state awards, including two Christopher Awards and an Edgar Award. His popular works include About Average, Troublemaker, Extra Credit, Lost and Found, No Talking, Room One, Lunch Money, and more. He is also the author of the Benjamin Pratt & the Keepers of the School series. He lives with his wife in Maine and has four grown children. Visit him at AndrewClements.com.