Five Ways Families Can Cope

With Setbacks

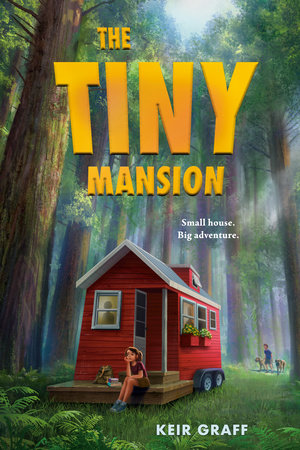

by Keir Graff

When I started writing The Tiny Mansion in early 2018, I never imagined that two of its key components — isolation and wildfire — would be playing out in such a big way when the book was released into the world. Having real life overtake my fiction feels like an awesome responsibility. I find myself asking, Did I get it right? Are there useful lessons in my book?

Twelve-year-old Dagmar is a brave and stubborn girl whose resourceful, artistically-inclined Oakland family finds itself evicted from their apartment and forced to live in a tiny house her father built for a client who refused to pay. Heading north, they end up squatting on land adjacent to a redwood forest — which is owned by a temperamental, reclusive tech billionaire with a miserable son.

In many ways, Dagmar’s sudden severance from her friends, and her family’s isolation, echo our quarantine experiences. With normal outlets for energies and emotions no longer available, our attention is focused inward, which creates an awful lot of stress. Tween Dagmar and her five-year-old half-brother Santi squabble, and their parents Trent and Leya are also on edge.

Find Your Footing

Despite the uncertainty of their precarious new position, the parents quickly resume their normal routines: her artist stepmother makes art in the forest, and her handyman father occupies himself by building a drystone wall. Santi engages in imaginative play with sticks and bugs while Dagmar seeks solace — and finds adventure — in the woods.

I don’t write didactic fiction — I believe young readers are capable of drawing their own good conclusions from the available evidence — but I realize now that I wrote my adults the way I hope I’d react. When families are faced with setbacks, we can regain our footing by reconnecting with familiar activities. If external upheaval is met by a chaotic response, it is destabilizing, but reestablishing normal rhythms allows a family to find its footing and make a rational plan for the future. And our kids are always watching what we do.

Go Outside

I think it also helps to go outside. Many Americans were driven outdoors this year simply because it’s the safest place to have fun and socialize. No doubt they also rediscovered the calming, restorative effect of being outdoors. Sunlight, fresh air, and exercise are not only good for our physical health, they elevate our mental health, too. Though I live in Chicago, my own family was able to reboot and recharge through regular trips to nearby nature preserves, where even a short walk reminded us birds were still singing, frogs were still croaking, and bugs were still buzzing. We all need regular reminders that us and our worries — while important — are only a small part of the world.

In Case of Emergency

Of course, when nature itself becomes dangerous, we are reminded of how little we can control. In the climax of The Tiny Mansion, an unusually hot coastal summer erupts into a raging wildfire, and Dagmar’s desire to go home is superseded by an existential problem: How can she help get everyone to safety?

This is a middle grade adventure, not nonfiction, and young readers will intuitively understand they are not responsible for herding a group of distracted grownups to safety. But they may also wonder what to do when crises happen so fast we don’t have time to think.

In times like these, we must focus first on our most basic needs — physical safety, shelter, food — before we can regroup and start over. Ironically, the wall Dagmar’s dad builds, which she thought of as a somewhat boring hobby, turns out to have a practical use during the emergency, which is a metaphor for the way our core strengths and interests can be foundations in times of crisis.

Find Time for Fun

Once physical safety is assured, we shouldn’t wait too long to fill our social and emotional needs in whatever small ways we can. Survival is a short-term goal — for the long run, we need to thrive. Displaced by wildfire and sheltering in a middle school gym, Dagmar’s family finds themselves with even less than they started with. What is Dagmar’s first response? To explore her surroundings. And then to play.

Talk It Over

Even though Dagmar’s blended family is fairly close-knit, they do sometimes struggle to communicate. One source of strength is that her father always keeps the lines of dialogue open. We should all be open to hearing our kids’ concerns, but we don’t have to wait for a crisis. Make a habit of talking things over. For example, almost every book, movie, or TV show depicts a character or family facing a setback. When watching together, use these as conversational openings: How did the character handle adversity? Could they have done anything differently? How would our family face the same situation?

What we can imagine, we can overcome.