Why Dictionaries Still Matter for

Kids Today

by Kory Stamper

Though I write dictionaries for a living, I have a secret shame: My children don’t particularly like dictionaries. When I consider their perspective, I can hardly blame them. Dictionaries are unwieldy books, written in an esoteric academic language that’s as alien as Klingon; you have to know how to spell the word you’re looking up to find it; they take up time and space, two things that are at a premium in today’s modern household. Besides, my kids chirp, there’s the Internet. The Internet, they assure me, has an answer for everything.

And it certainly seems like that’s true. Need to fix the toilet flapper? YouTube. Want to tile your backsplash with pennies? Pinterest. The car is making a weird noise? There’s an app for that. Indeed, all you need to do today to look up a word is Google it, and voila: a definition.

There’s no denying that online references make homework easier and faster, and I’d be a fool to suggest that we ignore how handy they are. Sometimes you need to get from point A (vocab homework) to point B (the answer) quickly. But there is a case to be made for the meandering through the alphabet that a print dictionary requires of its user.

My parents had a bargain-basement paperback dictionary stuffed into a drawer of the credenza, and it was only unearthed from beneath a pile of scrap paper for crosswords and Scrabble games. When I had homework to do, I’d bleat, “Mom, what does ‘ineffable’ mean?” and she’d just point at the drawer. Homework is drudgery, but a print dictionary offers the opportunity for busy-looking procrastination and some serendipitous joy along the way. We’ve all looked up a word and then idly scanned the page, only to find some hidden delight: the historically accurate ridiculousness of “gardyloo” (“used in Edinburgh as a warning cry when it was customary to throw slops from the windows into the streets”); the pointed, clinical aptness of “dispraise” (“to comment on with disapproval”); the smirking chewiness of “codswallop” (“nonsense”). These are secret gems which make English sparkle, but you won’t find them in an online reference unless you know to go looking for them.

You might need to prime the pump: Let your child watch you discover some of these gems. Say them aloud, roll them around your mouth, and have a giggle over how they sound. English is a goofy language sometimes. Even the experts think so.

Having a print dictionary around also provides opportunities for adults and children to have significant discussions about words — not just what they mean, but what sort of world they exist within. Let’s be real: We all know that the first things kids do when they get their hands on a dictionary is look up curse words. This is just an inevitability, the lexical equivalent of death and taxes, and one that’s hard to ignore when your dictionary naturally opens to the page that begins with “fuchsia” after your preteen has been using it for homework. Dictionaries record the language as it’s used — good, bad, and ugly — but they do it in a way that is objective and scholarly. It opens up room for a curious child to ask, “But why is that a bad word?” Maybe you don’t know. But now there’s an opportunity to find out together and to talk about why our words, and the contexts we use them in, matter.

And in the end, that’s what dictionaries help show us: that words of all kinds have a place in our lives. Regardless of whether they’re good, bad, ugly, ridiculous, funny-sounding, or boring, words are one of the primary ways that we share our history, our hopes, and ourselves with the people around us, and dictionaries are one record of that. That they might encourage your child to say “codswallop” is just an added bonus.

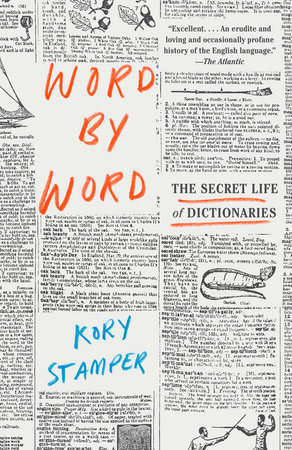

To learn more about the fascinating world of dictionaries and how they’re made, check out Kory Stamper’s Word by Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries.