Quick — name a women’s suffrage activist. Did I hear you say Susan B. Anthony? Great! Now, name another woman who fought for women’s right to vote.

Hello? Anyone?

Ok, maybe (hopefully!) you were able to name someone else. Maybe you’re still listing off women’s suffrage activists! If you are, that’s fantastic. If you’re stuck, that’s ok. Susan B. Anthony was an incredibly important figure in the suffrage movement. But she was also not the only woman doing this work — not by a long shot. So let’s learn about some of the other women who devoted their lives to ensuring that the women in our lives get to cast a ballot in November.

SWEEPSTAKES: Enter to Win a Rad American History Prize Pack

The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of women gaining the right to vote in America. On August 18, 1920, Congress finally ratified the 19th amendment, which forbid states from denying the right to vote “on account of sex.” It was the culmination of an almost century-long quest for voting equality in America, but it was by no means the end of that battle. Though the 19th amendment gave women the right to vote, it didn’t change the racist laws that prevented millions of non-white women and men from voting — literacy tests, poll taxes, and other Jim Crow-era policies routinely prevented people of color and non-English speaking citizens from voting up until the legislative victories of the civil rights movement era. Though these laws have been overturned, voter suppression is still a problem today. In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a key part of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, prompting Ruth Bader Ginsburg to write that throwing out a law that is working is like “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

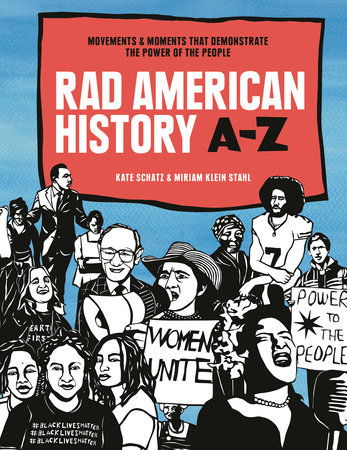

Readers will learn about suffrage, the women’s rights movement, and voting rights in Rad American History A-Z, the new book that I co-created with illustrator Miriam Klein Stahl. It’s the latest in the Rad Women series that we’ve been working on since 2015, and unlike the previous books, this one focuses on historical moments and movements rather than individual historical figures.

By focusing on the stories of women — whose stories aren’t told as often and whose names aren’t as familiar — we hope to expand the roster of potential heroes and icons for people of all ages and genders. We want readers to see that important moments and movements in history weren’t the work of one single person — Abraham Lincoln did not single-handedly “end slavery”; Harriet Tubman did not “invent” the Underground Railroad; Rosa Parks was not the only black woman involved in the civil rights movement; Cesar Chavez did not form the United Farm Workers by himself. And Susan B. Anthony didn’t get us the vote on her own. These statements are not to diminish or dismiss the impact of these great Americans by any means, but we want to acknowledge the accomplishments of all the other people who were there, too, and to remind readers of how interconnected and complex these histories are.

In honor of Women’s History Month, and the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment, here are a few of the lesser-known courageous American women who fought, marched, organized, testified, published, strategized, and agitated for the enfranchisement of women. All of these crusaders are featured in Rad American History A-Z, but there is much more to learn and say about each one.

-

The Forten Women

The Fortens were one of the most prominent black families in Philadelphia during the early 19th century. James and Charlotte Forten were both born free in the late 18th century, and James became a successful sailmaker after the Revolutionary War. Their five children, including daughters Sarah, Harriet, and Margaretta, grew up in a home that regularly hosted prominent abolitionists, as well as fugitive slaves. 1833, Charlotte and her daughters founded the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society, the first American biracial organization of female abolitionists. All three daughters went on to become prolific writers, educators, organizers, and public speakers — lecturing extensively about suffrage for women and black Americans and working as members of numerous suffrage organizations.

Sadly, there aren’t any children’s books about them — yet. But the Fortens are a wonderful example of a family who worked together for justice and equality. Older kids might be interested in tracing the generations of Fortens (and Purvis’— two of the sisters married into the similarly progressive Purvis family). Their story is also important because it reminds us of two crucial but often overlooked aspects of suffrage history: that the women’s suffrage movement emerged directly from the abolitionist movement, and that black women were key players in the movement from the very beginning.

-

Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott was a hardcore Quaker who committed her life to the pursuit of justice for all human beings — her writings, speeches, and actions are powerful antidotes to the argument that white women of the 19th century who espoused racist ideas were “products of the time” and “didn’t know any better.” Mott was a key figure in the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, which was the first women’s rights convention, and presided over much of it.

But women’s rights wasn’t her only cause: before she arrived at Seneca Falls, she met with members of the Seneca Nation to discuss Native American rights, former slaves who’d escaped to Canada, and inmates at a nearby prison. Surprisingly, Lucretia Mott wasn’t initially a suffrage activist — she actually opposed Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s resolution demanding voting rights for women. It’s not that she didn’t think women should be able to vote, but rather she felt that the entire American political and economic system was completely bound to the evil institution of slavery. To her, voting was active participation in an immoral system. She changed her tune eventually, and after the Civil War she was elected as the first president of the American Equal Rights Society, which advocated for universal suffrage for black Americans and women.

-

Matilda Joslyn Gage

Born in 1826, Gage was a suffragist, a Native American rights activist, an abolitionist, and a writer (as well as the beloved mother-in-law of L. Frank Baum, author of The Wizard of Oz!). Along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, she co-authored History of Woman Suffrage, the six volume, 5,700-page tome that was published over the course of several decades. However, Gage’s views on suffrage tended to be more radical than that of Anthony and Stanton: Gage actively supported the 15th amendment and voting rights for black men, unlike Stanton and Anthony who remained narrowly focused on the cause of white women’s suffrage. Gage also rejected the arguments of conservative Christian women who supported suffrage in order to advance causes like temperance.

Gage was a believer in true equality, and like Lucretia Mott she campaigned for the rights of Native Americans as well. She became close with local indigenous women and witnessed firsthand the rights and liberties their culture afforded them. Gage was adopted into the Wolf Clan of the Mohawk Nation, and was able to vote on tribal matters along with other women. She argued that the racist attitude of many towards Native Americans was, in fact, quite backwards: the modern world was indebted to the Mohawks and other members of the Iroquois Nation, she argued, “for its first conception of inherent rights…and the establishment of a civilized government.”

-

Mary Church Terrell

Mary Church Terrell lived to be almost 100, and her activism began with the suffrage movement and continued all the way through to the early days of the civil rights movement. She was born in Tennessee in 1863 to a father who’d once been enslaved and then became a millionaire landowner. She got her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees at Oberlin College and, after becoming the first African American woman appointed to the school board in the District of Columbia, she emerged as a leader among black women suffragists and clubwomen of the late 19th and early 20th century.

She was instrumental in building the national political power of black women’s clubs, which were grass-roots organizations made up mostly of educated, middle-class black women who were part of larger progressive reform efforts, including child welfare, education, job training, healthcare, voter registration, and political lobbying. These clubs played a huge role in the suffrage movement, persisting even when faced with intense racism from white suffragists who saw their involvement as a threat to the movement’s success. Terrell helped bring the clubs together on the national level, and was elected the first president of the National Association of Colored Women. She gave powerful speeches about race, gender, and political power to her white counterparts, reminding white women that excluding black women from voting because of race was no different than excluding white women because of gender. She organized a pro-suffrage strike of Howard University women the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, helped found the NAACP, and, at age 86, helped desegregate restaurants in Washington, D.C.

-

Lucy Burns

By the dawn of the 20th century, many of the first and second generation of suffrage activists were deceased or elderly (the latter didn’t necessarily slow them down — Susan B. Anthony turned 80 in 1900, and before her death in 1906 she spoke at six conventions and four congressional hearings, traveled to 18 states and to Europe, and completed the fourth volume of History of Woman Suffrage). Many younger activists became frustrated by the slow pace of progress, and began adopting new tactics that were often more aggressive and confrontational. Lucy Burns was one of them. After witnessing the more radical tactics of British suffragists like Emmaline Pankhurst (and getting arrested alongside them), Burns sought to bring fresh energy to the movement.

Among many efforts, she and Alice Paul started the National Women’s Party and organized the Silent Sentinels — a rotating group of women who silently picketed the White House every day for nearly two years. When the U.S. entered World War I, she refused to sideline the suffrage effort as many other less radical suffragists did. Burns was arrested many times, and in November 1917, she and 32 other “Sentinels” were arrested, imprisoned, and brutally beaten by prison guards at Occoquan Workhouse — a Virginia prison. To protest the beating, Burns went on a hunger strike and was force-fed through a nose tube. She and the Sentinels resumed their protests after their relief, and eventually President Wilson took action and convened a special session of Congress in 1919 to begin the process of passing the 19th amendment. Burns and the National Women’s Party lobbied hard in many states in order to achieve ratification of the amendment.